Introduction

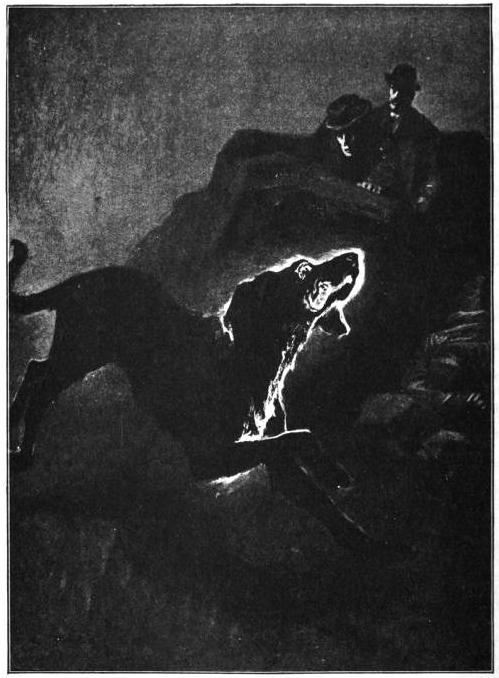

When Henry Baskerville, the eponymous baronet of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, arrives at his family’s manor, he finds himself heir not only to a country estate but an assortment of potential morbidities, including a lethal family curse, a hellhound, an escaped convict, and Sherlock Holmes. Faced with these complications, however, the young scion decides that the problem is primarily one of lighting. “‘It’s no wonder my uncle felt as if trouble were coming on him in such a place as this,’ said [Baskerville]. ‘It’s enough to scare any man. I’ll have a row of electric lamps up here inside of six months, and you won’t know it again, with a thousand candle-power Swan and Edison right here in front of the hall door.’”

This is a lot of pressure to put on a light. When Doyle’s novel was first serialized in 1902, however, lighting was serving as the catch-all representative for any number of concepts: science, engineering, knowledge, the West, beautiful cities, public safety, Paris, Manifest Destiny, wealth, religion, exploration, modernity, the Statue of Liberty, the Harper publishing house, and civilization itself. Illumination was certainly equipped to take on a dog.

As it happened, neither hound nor Holmes proved particularly deterred by exterior lighting, but the idea that illumination was progress, and that progress was safety, zipped undaunted through the twentieth century and remains alive and well in the twenty-first, as modern-day Henry Baskervilles contemplate floodlighting their suburban homes in the name of safety, often encouraged by their local police departments. This assumption is so ingrained, in fact, that it was not until the 1990s that large-scale studies set out to qualitatively examine whether lighting and crime really did exist in inverse proportion. The answer: the link is far fuzzier than decades of public and security policy ever anticipated.

What is not at doubt, however, is that light makes us feel safer. Yet as artificial light—particularly artificial light at night, or ALAN—has exploded across the globe, the security benefits are contradictory at best. For the natural world, however, the impact has been generally more straightforward: fairly disastrous. At least in passing, most Americans have heard of the fatal disorientation of seaside lights on nesting sea turtles and hatchlings, wandering onto roadways instead of the Atlantic. More obscure is the plight of the tammar wallaby in Australia, whose summer solstice-tied reproductive cycle has gone into free fall thanks to artificial light, or the hundreds of millions of migrating birds led fatally astray by nocturnal lighting each year. And the impact of ALAN is not limited to the cute. One study from Germany suggests that German street lights alone could take out 60 billion insects (that’s a “b”) in a single summer. Even the famous deer-in-the-headlights trope has its roots in the physiology of a deer’s eyes, which render it literally blind and frozen; even if it manages to avoid becoming roadkill, its vision will be compromised for another ten to forty minutes, leaving it vulnerable to predation.

That being said, most of us would choose a brightly-lit street over a dark alley, and the burden of darkness is one that falls unevenly. The psychological toll on a man who fears being mugged while crossing a dark and lonely parking lot is of a different grade than the woman who worries about being raped and murdered. Similarly, a poorly lit neighborhood carries a different pressure for minority or poorer residents, who may see in it a reflection of entrenched, systemic negligence of their communities and needs.

Yet many advocates of Dark Sky initiatives tend to appeal to either the natural (consider the turtles) or the poetic: van Gogh’s Starry Night, say, or the majesty of Milky Way as being integral to the human experience. And, to be sure, seeing the Milky Way is perhaps the closest that we can come to touching transcendence—but this is not precisely helpful when it comes to personal security. Some proponents of limited ALAN, looking at the increasingly doubtful links between night lighting and crime prevention, have noted that there is a gap between feeling safe and being safe. This is true, but it may also be something of a moot point. For one, we humans tend to base our decisions more on what we feel than what we know. For another, our most disenfranchised communities have historically had very real existential threats routinely derided as being exaggerated, “all in your head,” or otherwise nonexistent. Given this, dismissing a feeling of security on the basis of it being, well, a feeling, risks ringing hollow. Asking society’s most vulnerable to abandon their sense of security for the wellbeing of a wallaby veers into callousness.

However, ALAN does represent a serious threat, to humans as well as to the natural environment. In these times, when everything comes with a tinge of the apocalyptic (pandemic, climate change, Mayan prophesies), it is worth thinking of ALAN less as a distinct peril than as the convergence point of so many others: of security, disease, global warming, and environmental collapse.

It is these perils that the Zoological Lighting Institute’s inaugural blog series, focusing on light and security, aims to interrogate. We’ll start by looking at the historic links between artificial light and public safety, and see how these links still inform our policies today. Then we’ll get into the tricky territory of looking at the data on lighting and crime to see if these policies actually work. As security is not a question of crime alone, we’ll also look at the impact of light (especially ALAN) on health and the environment. Finally, we’ll round this series out by looking at possible solutions—ones that let us both feel safe and be safe—and offer some recommendations from ZLI. At its heart, however, this series will be guided by three simple questions.

What is the threat of artificial light, exactly? How did we get to this place? And where are we meant to go?